Bovine Viral Diarrhea

Bovine viral diarrhea is a worldwide-distributed disease, with varying prevalence across countries and a significant financial impact. It is caused by infection from the bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV).

The disease is primarily spread and maintained in cattle populations by persistently infected (PI) individuals. Persistent infection occurs from fetal infection in early gestation following infection of the dam.

The majority of control programs aim to eliminate PI cattle1 and, therefore, the source of continuing infection.

BVDV is a pestivirus of the Flaviviridae family.

- Two genotypes: BVDV-1 and BVDV-2, on the basis of antigenic and genetic differences

- Two biotypes: Non-cytopathic (NCP) and cytopathic (CP); CP strains are responsible for causing mucosal disease (MD) in animals that are persistently infected with BVD

The BVDV-1 genotype is isolated more frequently than the BVDV-2 genotype2.

When naïve, non-pregnant cattle are exposed to the virus, they undergo a short period of viraemia that may last between three and 12 days, turning into transient infections. Most are subclinical.

Clinical signs include:

- Pyrexia

- Depression

- Anorexia

- Diarrhea

- Respiratory signs, which include nasal discharge and coughing

- Leukopenia with lymphopenia

BVDV infection may lower immunity to other infectious diseases such as salmonellosis, respiratory infections or mastitis.

Virulent strains of BVDV are associated with severe presentations of transient BVD that, in addition to the clinical signs described, cause thrombocytopenia and mucosal ulceration and could be confused with mucosal disease (MD).

Severe BVD has usually been associated with BVDV-2, but it could also be caused by BVDV-1. In pregnant cows, the effects on the dam and fetus depend on the stage of gestation. Persistent infection only develops if the dam is exposed to BVDV at less than 120 days of pregnancy. An animal cannot become persistently infected after it is born3.

PI animals with BVDV develop neutralizing antibodies and are clinically recovered between two and three weeks post infection. After natural exposure to BVDV, antibodies have been shown to last for at least three years, but it is believed the immunity may be lifelong4.

Mucosal Disease

Animals with MD present ulceration of the gastrointestinal tract, from the oral cavity (gums, tongue, cheeks and palate) to the abomasum and small intestine. Common findings such as inter-digital and coronary band ulceration result in severe lameness. Affected animals are usually pyrexic, anorexic, have fever, do not eat, are depressed and suffer from severe diarrhea that can present fresh blood and/or dark black feces.

The presentation of MD is usually acute and animals die within a few days or weeks of onset of clinical signs. PI cattle traditionally have poor growth rates and are susceptible to secondary diseases, with higher mortality rates. However, many PI cattle may appear clinically normal and live for years, being able to reproduce and generate new PI calves.

Chronic Infection

BVD can also be a subclinical chronic disease. A recent study5 reported the presence of two bulls that were clinically normal, serocompetent and BVDV antigen negative, but presented very high antibody titres against BVDV. They had BVDV infections localized in the testes and were able to successfully transmit the disease via AI.

Eliminating PI cattle requires using accurate diagnostic tests for the detection of BVD virus, antigen or specific antibodies.

The challenge to BVDV diagnosis and control is the selection of the appropriate test for different situations.

Pre- and postnatal infection with BVDV is associated with a variety of disease syndromes:

- Immune suppression

- Congenital defects

- Mucosal disease

- Abortion

Fetal infection before 125 days of gestation can cause fetal death and abortion, reabsorption, mummification, developmental abnormalities or fetal immunotolerance and persistent infection.

What do you see in the field?

- Repeat breeders

- Low conception rates

- Extended inter-calving intervals

- High number of examinations per cows

Reduction in Conception Rates

Acute infection with BVDV –> Inflammatory changes within the reproductive ovarian tissue (in both the follicles and the forming corpora lutea) –> Inadequate follicular and luteal function –> Fertility failure6

Impaired Follicular Growth

Several studies have reported that the pattern of follicular growth was clearly disrupted, with a smaller diameter in the preovulatory follicle and lesser maximum diameter of the ovulatory follicle in the cows infected with BVDV7.

Inadequate Estradiol Production

The differences in the follicular growth in the infected cows is associated with disrupted estradiol secretion pattern with generally lower estradiol levels and especially delayed preovulatory estradiol peak8.

Delay in Estrus Expression and Delayed LH Peak

A changed pattern of estradiol production –> Delay in the onset of estrus behavior and the poorer expression of estrus signs in heifers infected with BVDV6

The same study examined the endocrine profiles of the infected heifers and revealed that 83% of them had no normal preovulatory peak of estradiol and LH:

Inadequate follicular growth and estradiol secretion –> Incapable of stimulating the proper LH secretion

A delayed and inadequate preovulatory LH surge –> Delayed ovulation, which may negatively affect the quality of oocytes and also the developmental potential of embryos

Inadequate Progesterone Production

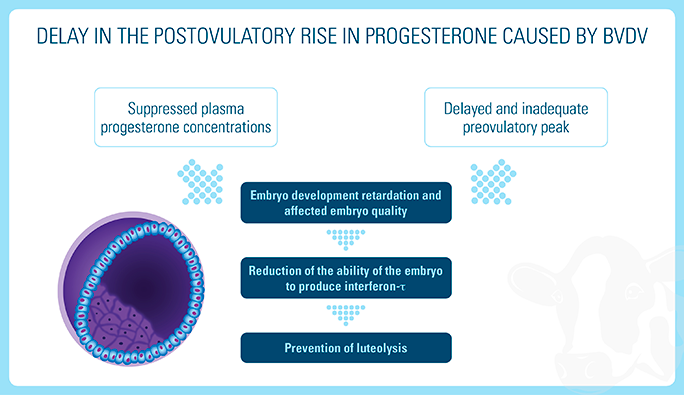

The cell-free viraemia observed around the time of breeding showed a delay in the postovulatory rise in progesterone as well as generally lower progesterone concentrations between three and 11 days after ovulation6.

A large-scale statistical analysis of the effects of BVDV infection on fertility in dairy herds in Brittany (Western France) showed that cows in herds exposed to an ongoing BVDV infection had a significantly higher risk of late return to service (later than 21 days) than cows in herds presumed to be not infected for a long time or not recently infected7.

There is currently no treatment available, only solutions for secondary infections.

- Tight biosecurity measures will limit the exposure of the animals to the virus.

- Vaccinating cattle can prevent cell-free viraemia and transplacental infection.

- Lindberg, Ann & Alenius, Stefan. (1999). Principles for eradication of bovine viral diarrhoea virus (BVDV) infection in cattle populations. Veterinary Microbiology. 64. 197-222. 10.1016/S0378-1135(98)00270-3.

- Walz PH.Bovine Diarrhea Virus. Chapter 24. Food Animal Practice (Fifth Edition). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-141603591-6.10024-7

- Bovine Viral Diarrhea: Background, Management and Control https://www.vet.cornell.edu/animal-health-diagnostic-center/programs/nyschap/modules-documents/bovine-viral-diarrhea-background-management-and-control.

- Fredriksen B., Sandvik T., Loken T., Odegaard S. A. Level and duration of serum antibodies in cattle infected experimentally and naturally with bovine virus diarrhoea virus. Vet. Rec. 1999;144:111–114.

- Newcomer BW, Toohey-Kurth K, Zhang Y et al (2014). Laboratory diagnosis and transmissibility of bovine viral diarrhea virus from a bull with a persistent testicular infection, Vet Microbiol 170(3-4): 246-257.

- Fray MD, Mann GE, Bleach ECL, Knight PG, Clarke MC, Charleston B.2002. Modulation of sex hormone secretion in cows by acute infection with bovine viral diarrhoea virus. Reproduction, 123, 281-289.

- Robert A, Beaudeau F, Seegers H, Joly A, Philipot JM. 2004. Large scale assessment of the effect associated with bovine viral diarrhoea virus infection on fertility of dairy cows in 6149 dairy herds in Brittany (Western France). Theriogenology. 61(1):117-27.